Imagine a carousel spinning with children clustered toward its center, while a lone leaf dances along the outer rim. The leaf’s movement at the edge isn’t just a simple speed—it's a precise measurement of tangential velocity, a vector that captures how quickly an object moves along a circular path at a specific point. For engineers designing centrifugal systems, astronomers analyzing planetary rotations, or physicists exploring rotational dynamics, grasping the nuances of tangential velocity is critical. Each of these domains relies on understanding how motion at the periphery influences systems, energy transfer, and even safety protocols. From the everyday amusement ride to the cosmic scale, tangential velocity is a compelling anchor in the mechanics of rotation.

Unveiling the Concept of Tangential Velocity in Rotational Motion

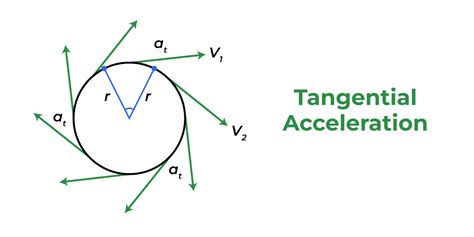

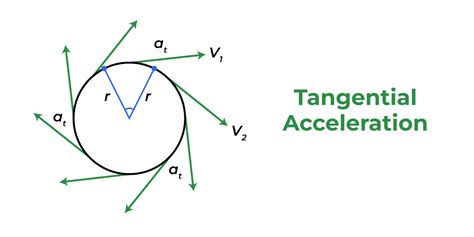

At its core, tangential velocity describes the linear speed of a point located at a specific radius from a rotation center, moving along a tangent to its circular path. While angular velocity ((\omega)) measures how quickly the system rotates in radians per second, tangential velocity ((v_t)) tells us how fast a particular point on the rim travels through space. The fundamental relationship between these two quantities is expressed as:

v_t = r \times \omegaThis straightforward equation encapsulates a world where distance from the center directly influences linear speed. As you move further from the axis of rotation, the tangential velocity increases proportionally, assuming a constant angular velocity. For professionals engaged in various disciplines, this relationship underpins calculations that range from designing efficient turbines to studying celestial bodies’ rotation rates.

Practical Applications of Tangential Velocity

In everyday engineering contexts, calculating tangential velocity informs the design of rotating machinery. For instance, in selecting gear ratios for turbines, high tangential velocities can cause material fatigue or mechanical failure. Consequently, understanding the velocity at the edge—say, a turbine blade tip—directly influences material choices, safety margins, and operational parameters.

In astrophysics, the concept extends to planetary rotation. Taking the Earth as an example, with an average radius of approximately 6,371 km and a rotational period of about 24 hours, its tangential velocity at the equator computes to roughly 1,670 km/h. This velocity profoundly affects climate systems, atmosphere dynamics, and even how satellites orbit the planet.

Similarly, in sports science, athletes use an understanding of tangential velocity to optimize equipment, such as the spin of a basketball or the rotation of a baseball pitch, often harnessing the physics of tangential motion to improve performance.

Measuring and Calculating Tangential Velocity in Real-World Scenarios

Practitioners employ a combination of direct measurement and mathematical modeling. A typical method involves determining the radius of rotation—measured in meters—and the angular velocity—expressed in radians per second. Using high-speed cameras or motion sensors, engineers and scientists extract angular velocity data, which feed into the equation (v_t = r \times \omega) for precise calculation.

For example, consider a wind turbine with blades extending 50 meters from the hub. If the turbine spins at 1.2 radians per second (roughly 11.46 RPM), the maximum tangential velocity at the blade tips can be calculated as:

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Radius ® | 50 meters |

| Angular velocity ((\omega)) | 1.2 radians/sec |

| Tangential velocity ((v_t)) | 60 meters/sec (or 216 km/h) |

This velocity signals the material stresses at the blade tip, critical for material selection and operational safety, especially to prevent fluttering or failure under turbulent conditions.

Historical Context and Evolution of Rotational Motion Understanding

The study of rotational motion, including tangential velocity, finds its roots in classical mechanics—most notably through the works of Galileo Galilei and Sir Isaac Newton. Galileo’s experiments with pendulums and rolling balls provided early insights into motion, setting the stage for Newton’s formulation of the laws of motion. Newton’s Second Law ((F = ma)) extended into rotational dynamics with the introduction of torque and angular acceleration, laying the groundwork to relate angular velocity and tangential velocity in a comprehensive framework.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, advances in mathematical modeling and technological measurements—such as high-speed cameras, gyroscopes, and laser Doppler velocimetry—refined the precision with which scientists could evaluate motions at the edge of rotating bodies. These developments facilitated sophisticated simulations of planetary systems, turbines, and even particle accelerators, marking milestones in both theoretical understanding and practical applications.

Nuances and Limitations in Understanding Tangential Velocity

While the fundamental relationship (v_t = r \times \omega) appears straightforward, real-world scenarios often introduce complexities. Non-uniform rotational speeds, such as those in gyroscopes experiencing precession, mean that local tangential velocities vary dynamically. Similarly, in systems with eccentric rotations or oscillations, the simple linear relationship must be augmented with time-dependent models.

Moreover, material properties become critical at high tangential velocities. For example, at velocities approaching the speed of sound within the material, shock waves and structural instabilities pose significant risks. Engineers employ finite element analysis to predict these effects, ensuring safety margins and durability.

Optimizing Systems Using Tangential Velocity Insights

Understanding tangential velocity allows for the strategic enhancement of system efficiency. In wind energy, for instance, the goal is to maximize energy capture while avoiding blade tip speeds that cause excessive wear or noise. Variable pitch blades help modify angular velocity dynamically, maintaining optimal tangential velocities amidst changing wind conditions.

In aerospace engineering, the design of high-performance turbines and jet engines hinges on precise control of edge velocities to maximize thrust without provoking material fatigue. These systems often operate near critical velocity thresholds, where small adjustments drastically improve lifespan and efficiency.

Future Directions and Innovations in Rotational Dynamics

Emerging fields like nano-mechanical systems and quantum rotors push the boundaries of classical tangential velocity concepts. At nano scales, quantum effects influence motion, and new measurement techniques—such as atomic force microscopy—are employed to analyze motion with unprecedented precision. Similarly, in space exploration, innovative propulsion systems consider rotational dynamics to optimize fuel consumption and transfer speeds.

Furthermore, advancements in smart materials—able to alter their properties in response to velocity and stress—offer promising avenues for managing high tangential velocities without sacrificing durability. As computational power grows, simulations integrating complex physical effects become more accurate, enabling better predictions and innovations.

Key Points

- Understanding the direct proportionality between radius and tangential velocity is essential in systems design.

- Accurate measurement of angular velocity combined with radius informs safety and performance thresholds.

- Historical developments trace the evolution from classical mechanics to modern computational modeling.

- Material science and structural analysis underpin safety considerations at high edge velocities.

- Future innovations depend heavily on integrating quantum physics, nanotechnology, and smart materials.

How does tangential velocity differ from linear velocity?

+While often used interchangeably in casual contexts, tangential velocity specifically refers to the linear speed of a point on a rotating body’s edge, directed along the tangent. Linear velocity, however, broadly describes any object’s speed along a straight path, which may or may not be related to rotational motion. In rotational systems, tangential velocity is a particular case of linear velocity defined at a specific radius.

What factors influence the maximum tangential velocity of a rotating system?

+Several factors influence maximum tangential velocity, including material strength, system geometry, rotational speed, and environmental conditions. Material fatigue thresholds determine how fast the rims or edges can spin without failure. System design constraints, such as gear ratios and energy input, also play critical roles. Additionally, external forces like aerodynamic drag or magnetic fields may impact rotational limits.

Why is understanding tangential velocity important in aerospace engineering?

+In aerospace contexts, tangent velocity informs the design of turbine blades, propellers, and rotors, balancing maximizing energy transfer with structural integrity. High tangential velocities could induce vibrations or fatigue, risking component failure. Precise control ensures optimal performance, safety, and lifespan of engines and spinning instruments in spacecraft or aircraft.

Can tangential velocity be changed during operation? If so, how?

+Yes, tangential velocity can be modulated by adjusting the system’s angular velocity ((\omega)) or changing the radius ®—for example, extending or retracting blades in some turbines. Variable speed drives in industrial machines and active control systems allow dynamic tuning to optimize performance or respond to external conditions.

What are some real-world safety considerations related to high tangential velocities?

+High tangential velocities generate significant centrifugal forces, which can lead to structural failure if materials are inadequate. Operational safety protocols include regular inspection, predictive maintenance, and limiting rotational speeds based on material fatigue limits. In aerospace, shielding and safety zones protect personnel from debris in case of rotor failure.