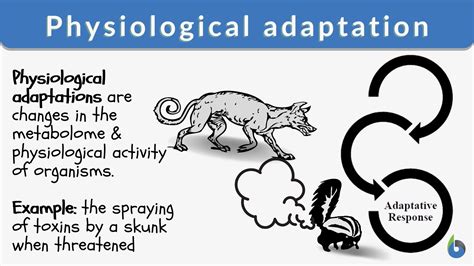

At the heart of biological evolution and survival lies an intricate dance between organisms and their environments, a process orchestrated through physiological adaptation. These adaptations are not merely responses to environmental stimuli but fundamental mechanisms that enable species to withstand, flourish, or falter amidst constant change. Yet, the journey to fully comprehend the nuances of physiological adaptation is fraught with pitfalls—mistakes that may distort scientific understanding and hinder effective application in fields ranging from medicine to ecology. To navigate this complex landscape, it is pivotal to explore the philosophical underpinnings of adaptation, recognize common errors, and illuminate paths toward more precise and holistic comprehension.

Understanding Physiological Adaptation: A Broader Perspective

When contemplating physiological adaptation, it is beneficial to transcend the immediate biological mechanisms and consider the overarching principle: life is an ongoing dialogue between internal capacities and external pressures. This dialogue is rooted in the principle of resilience—an organism’s ability to modify and optimize its internal processes to maintain homeostasis in variable conditions. Such resilience is not static but dynamic, derived from a confluence of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. Misinterpretations often arise when these factors are viewed in isolation or when the interconnectedness of systems is underappreciated.

Theoretical foundations of adaptation in biological sciences

The core theory stems from Darwinian notions of natural selection, which posits that advantageous traits become more prevalent over generations. However, physiological adaptation extends beyond this evolutionary timescale, embodying immediate or short-term responses that enhance survival. For example, thermoregulation exemplifies how organisms adjust their metabolic rates, blood flow, or behavior to withstand temperature fluctuations. These responses, though often studied in isolation, are components of a broader, integrated system that varies in scope and complexity across taxa.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Homeostasis | Stable internal environment maintained through feedback mechanisms; e.g., blood glucose regulation with a normal range around 70-110 mg/dL. |

| Acclimatization | Reversible physiological adjustments in response to environmental changes within an organism’s lifetime; e.g., increased red blood cell production at high altitude. |

| Phenotypic Plasticity | The capacity of an organism to alter its phenotype in response to environmental stimuli; e.g., eye color variation with age or seasonal skin color changes in animals. |

Common Pitfalls in Interpreting Physiological Adaptation

Numerous misconceptions persist in both academic literature and applied sciences regarding physiological adaptation. These errors cloud understanding and impede integrative approaches essential for tackling contemporary biological challenges.

Oversimplification of adaptation processes

One persistent error is the tendency to view adaptation as a linear, uniform process—implying that a specific environmental challenge yields a straightforward physiological response. In reality, adaptation involves multiple feedback loops, often with conflicting signals that must be reconciled within the organism’s integrative systems. For example, during cold exposure, vasoconstriction reduces heat loss, but prolonged constriction can impair tissue health. Such trade-offs exemplify the complexity often hidden behind simplified narratives.

Neglecting the role of energetic costs and trade-offs

Physiological adjustments incur energetic costs, and these trade-offs are frequently underappreciated in models of adaptation. An increase in metabolic activity to generate heat at high altitude, for instance, requires substantial nutrients and oxygen, which may be scarce. Overemphasizing the benefits while ignoring the costs creates an incomplete picture, risking misguided conclusions about the efficacy or sustainability of certain adaptations.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Energy expenditure | Increased metabolic rate in thermogenic tissues during cold stress can double basal metabolic needs, as seen in studies with Arctic mammals. |

| Trade-offs | Enhanced lung capacity in high-altitude natives may be balanced by other traits such as increased blood viscosity, illustrating adaptive trade-offs. |

Applying evolutionary context without sufficient nuance

Certain interpretations mistake current physiological states for direct evidence of adaptation, without considering historical and evolutionary contexts. For example, elevated hemoglobin levels in certain populations may be adaptive, but without understanding genetic background or alternative acclimatization strategies, these data can be misrepresented or oversimplified.

Nuanced Understanding: Integrating Multi-Scale Perspectives

To mitigate these common errors, a multi-layered perspective that integrates genetic, phenotypic, environmental, and evolutionary insights is essential. Such an approach recognizes that physiological adaptation is neither solely immediate nor solely evolutionary but exists along a continuum, influenced by temporal, spatial, and organismal factors.

Reconciling short-term plasticity with long-term evolution

Plastic responses provide flexibility within an organism’s lifetime, allowing rapid adjustment to environmental variations. Over generations, these responses can influence genetic selection, contributing to evolution. Recognizing this interplay averts the mistake of viewing plasticity as mere ‘short-term’ fixes, instead framing it as a vital component of adaptive potential.

For instance, in human populations residing at high altitudes, both immediate acclimatization (e.g., increased ventilation) and genetic adaptations (e.g., altered hemoglobin affinity) coexist. Understanding their interaction demands an appreciation of both processes within an evolutionary framework.

Incorporating systems biology for more accurate modeling

Systems biology offers tools to simulate and analyze the complex interactions underlying physiological responses. By integrating omics data—genomics, proteomics, metabolomics—researchers can delineate networks and pathways involved in adaptation, thus reducing errors stemming from oversimplification or isolated analyses.

| Related Entity | Key Data Point |

|---|---|

| Genomics | Genetic variants associated with high-altitude adaptation include EPAS1 in Tibetans, which influences hypoxia-inducible factors. |

| Proteomics | Protein expression changes in cold-exposed animals reveal increased activity of heat shock proteins and mitochondrial enzymes. |

Implications for Applied Sciences and Future Research

Understanding and avoiding common mistakes in ecological and biomedical applications dramatically influence how we address climate change resilience, disease resistance, and conservation strategies. For instance, misapprehending the plasticity limits of species might lead to underestimating their vulnerability, while overestimating innate adaptive capacities could result in overconfidence in current conservation approaches.

Precision medicine and adaptive therapies

In medicine, appreciating the distinction between plastic responses and genetic adaptations can inform personalized interventions. For example, tailoring hypoxia therapies for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) requires understanding both immediate tolerance mechanisms and long-term genetic predispositions, preventing costly oversights.

Environmental policy and ecosystem management

On an ecological scale, shaping resilient ecosystems demands recognizing the trade-offs and multi-scale interactions inherent to adaptation. Management plans that ignore energetic costs or potential maladaptations risk failures during environmental stressors.

Key Points

- Understanding habitual misconceptions avoids oversimplification of adaptation processes, clarifying the distinction between plasticity and evolution.

- Incorporating energetic and trade-off considerations leads to more realistic models of organismal resilience.

- Multi-scale, integrative frameworks bridge gap between immediate responses and long-term evolutionary shifts.

- Advanced methodologies such as systems biology offer nuanced insights, reducing interpretative errors.

- Practical applications benefit from precise, context-aware strategies in medicine, conservation, and environmental policy.

What distinguishes short-term physiological plasticity from genetic adaptation?

+Short-term plasticity involves reversible physiological changes within an organism’s lifetime, such as increased heart rate during exercise, while genetic adaptation refers to heritable changes accumulated over generations, like hemoglobin affinity in high-altitude populations.

How do trade-offs influence the evolutionary trajectory of adaptation?

+Trade-offs involve costs associated with adaptations; for example, increased muscle mass enhances strength but may decrease endurance due to higher metabolic demands. These costs shape the balance of adaptive traits over time.

Why is it important to study adaptation from a systems biology perspective?

+Systems biology integrates multiple data layers and models complex interactions, enabling a comprehensive understanding of how various physiological components coordinate during adaptation, reducing oversimplifications and uncovering emergent properties.