In the landscape of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV) occupy prominent, yet often misunderstood, positions. As global health authorities report millions of new cases annually, disentangling their biological, epidemiological, and clinical distinctions from other STDs becomes vital for effective prevention, diagnosis, and treatment strategies. Despite overlapping modes of transmission, HSV and HPV differ significantly in their pathogenesis, symptomatology, and long-term health implications, setting them apart from the broader spectrum of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). This review critically examines these viruses, contrasting them against other common STDs, and underscores their unique features within the context of modern sexual health management.

Biological Foundations and Epidemiological Trends of HSV and HPV

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), comprising two serotypes—HSV-1 and HSV-2—has a ubiquitous global prevalence. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 3.7 billion people under age 50 are infected with HSV-1 globally, primarily manifesting as oral herpes, while HSV-2 affects approximately 491 million people aged 15–49, predominantly causing genital herpes. This high prevalence reflects the virus’s ability to establish lifelong latency after initial infection, with periodic reactivations causing symptomatic outbreaks or subclinical shedding.

Conversely, HPV represents a family of over 200 virus types, with roughly 40 types infecting anogenital mucosa. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), persistent infection with high-risk HPV types—especially HPV 16 and 18—accounts for approximately 90% of cervical cancers. HPV’s high transmission efficiency, especially during vaginal, anal, or oral sex, and its capacity for immune evasion contribute to its persistent spread despite vaccination efforts. Both viruses demonstrate distinct age-specific prevalence peaks—HSV during young adulthood and HPV with a broader distribution across reproductive ages—mirroring their interaction with sexual activity behaviors.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Global prevalence | HSV: >3.7 billion with lifelong latency; HPV: >90% of sexually active women acquire some type by age 50 |

| Key high-risk types | HSV-1 and HSV-2; HPV types 16 and 18 |

| Latency and reactivation | HSV establishes latency in nerve ganglia; HPV persists episomally, integrating into host DNA in oncogenic cases |

Pathogenesis and Mode of Transmission: Divergent Routes and Implications

Both HSV and HPV primarily transmit through sexual contact, but the specifics of their entry and dissemination differ markedly. HSV gains entry via microabrasions in mucosal surfaces, establishing infection in epithelial cells followed by nerve invasion, facilitating latency. Recurrent outbreaks are driven by viral reactivation from neuronal latency, often triggered by immune suppression, stress, or other co-factors. Notably, asymptomatic shedding is common, complicating efforts to contain transmission among seemingly healthy carriers.

HPV exploits microtrauma during sexual activity to infect basal epithelium. Its lifecycle is closely tied to epithelial differentiation, with high-risk types integrating their DNA into host cells—potentially leading to oncogenic transformation. Unlike HSV, HPV does not establish true latency but instead persists episomally or integrates, sometimes inducing cellular dysplasia. Vaccination targeting major oncogenic types has significantly shifted the focus towards primary prevention of HPV-related cancers.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Transmission efficiency | HSV: moderate; HPV: high, especially with multiple partners |

| Latency site | HSV: trigeminal and sacral ganglia; HPV: episomal DNA in basal epithelial cells |

| Asymptomatic shedding | HSV: frequent; HPV: common shedding during infected epithelial cell turnover |

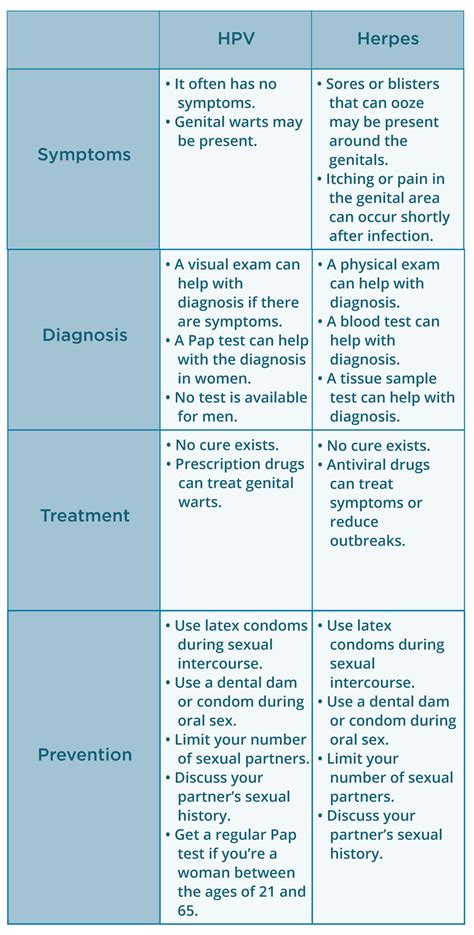

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Challenges

The symptomatic spectrum of HSV and HPV diverges significantly from other STDs like gonorrhea or chlamydia. Genital herpes typically presents as recurrent painful vesicular eruptions, with prodromal sensations preceding outbreaks. Atypical or asymptomatic shedding complicates diagnosis, often necessitating PCR-based detection or viral culture. Recurrent episodes impose psychological burdens and increase transmission risk.

In contrast, HPV infections are frequently asymptomatic, with high-risk types leading to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or other dysplastic lesions. External warts caused by low-risk HPV types may serve as visual markers, but many infections remain subclinical, only detected through cytology or molecular testing. The insidious nature of infection emphasizes the importance of routine screening, especially in high-risk populations.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | HSV: painful vesicles; HPV: often asymptomatic, warts or dysplastic changes |

| Diagnosis tools | HSV: PCR, culture; HPV: Pap smear, HPV DNA testing |

| Recurrence | HSV: frequent; HPV: persistent with potential to cause neoplastic transformation |

Health Consequences and Long-term Risks

While HSV’s hallmark is recurrent lifelong episodes, it also contributes to increased HIV acquisition risk due to mucosal inflammation. Additionally, neonatal herpes, though rare, carries significant morbidity. The psychological impact of herpes diagnosis—stigma, anxiety—further complicates long-term management.

HPV’s oncogenic potential is well established; persistent high-risk infection is the primary antecedent for cervical, anal, oropharyngeal, and other cancers. Vaccination efficacy—upwards of 90% prevention in vaccine-covered HPV types—has revolutionized preventive strategies, but disparities in coverage and screening remain persistent challenges.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Oncogenic risk | High-risk HPV types: 70% attributable to cervical cancers; some HPV types linked to other malignancies |

| Vertical transmission risks | Herpetic neonatal infections and HPV transmission during birth; significant but preventable with proper management |

| Psychosocial impact | Herpes: stigma and anxiety; HPV: fear of cancer and reproductive health concerns |

Counterpart: Comparison with Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases

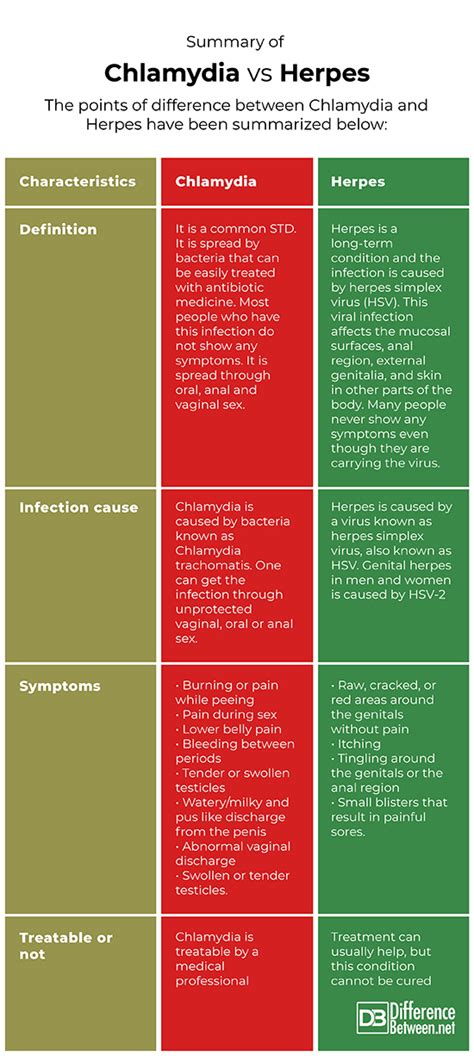

Other common STDs such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV differ fundamentally from HSV and HPV in several respects, notably in their transmission efficiency, clinical course, and response to treatment. Bacterial STDs like gonorrhea and chlamydia are curable with antibiotics and often have acute symptoms, whereas HSV and HPV are viral infections with persistent or latent phases, requiring different management approaches.

Syphilis, caused by Treponema pallidum, shares some similarities with HSV and HPV regarding latency and long-term complications but differs in transmission dynamics and treatment. HIV imposes a distinct challenge due to immune suppression and viral integration but also shares modes of sexual transmission. These distinctions highlight the need for nuanced understanding and tailored public health strategies.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Curability | Bacterial STDs: typically curable; viral STDs: often incurable but manageable |

| Latency | HSV: yes; HPV: episomal/integrated; Others: varies (latent or chronic) |

| Vaccination availability | Limited: HPV; None: for HSV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, HIV |

Emerging Strategies for Prevention and Management

Vaccine development has marked a pivotal shift—HPV vaccines covering several high-risk types have shown efficacy in reducing infection rates and associated cancers. Ongoing research aims to expand these vaccines to cover more strains and improve delivery methods, including therapeutic options for existing infections.

HSV management relies on antiviral suppressive therapy to reduce outbreaks and transmission, yet no vaccine exists currently. Novel approaches under investigation encompass therapeutic vaccines, gene editing technologies, and immune modulation strategies. Advances in rapid, point-of-care diagnostics enhance early detection, critical in controlling asymptomatic spread.

| Relevant Category | Substantive Data |

|---|---|

| Vaccine efficacy | HPV: up to 90% reduction in targeted strains; HSV: currently none, but under research |

| Therapeutic innovations | Gene therapy, immune-based vaccines, advanced antivirals |

| Screening advancements | Rapid PCR, self-sampling kits for HPV and HSV detection |

Conclusion: Navigating Differences for Better Outcomes

The distinctions between HSV and HPV, within the broader context of STDs, manifest as critical factors shaping clinical management, preventive strategies, and patient education. Recognizing their unique biological behaviors, transmission dynamics, and long-term health consequences enables tailored interventions—vaccination for HPV and antiviral therapy for HSV—that can substantially reduce disease burden. As advances in diagnostics, immunology, and vaccine science evolve, a nuanced understanding of these viruses continues to inform public health policies, emphasizing prevention and early detection as foundational pillars.

What are the main differences between HSV and HPV?

+HSV is a virus causing recurrent outbreaks with latency in nerve ganglia, transmitted via skin contact, often with painful lesions. HPV infects epithelial cells, primarily transmitted through microtrauma during sexual activity, and can lead to warts or cancers without symptoms. Their pathogenesis, persistence, and clinical features differ markedly.

How do prevention strategies differ for HSV and HPV?

+HPV prevention heavily relies on vaccination targeting major oncogenic types, combined with screening like Pap smears. HSV prevention focuses on condoms, behavioral modification, and antiviral suppressive therapy, with no available vaccine yet. Both benefit from education about asymptomatic shedding and safe sex practices.

Why are HPV-related cancers more preventable now?

+The development and widespread deployment of HPV vaccines targeting high-risk strains have significantly reduced infections and precancerous lesions, enabling early intervention and lowering cancer incidence. Routine screening further enhances early detection of dysplastic changes, improving prognosis.