In the realm of criminal law, few offenses have captured the public’s interest as consistently as grand larceny. Not only because of its societal implications but also due to the nuanced legal distinctions that separate it from other theft-related offenses, understanding the precise definition of grand larceny becomes critical for legal professionals, law enforcement, and the general public alike. Dissecting the concept reveals a layered architecture that hinges upon specific elements: value thresholds, jurisdictional statutes, and contextual variables that influence classification. This comprehensive examination seeks to elucidate the core attributes of grand larceny, trace its historical evolution, and provide practical insights into its application in contemporary jurisprudence.

Understanding Grand Larceny: Foundations and Legal Framework

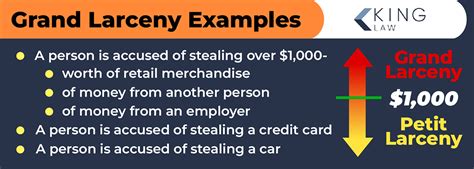

At its core, grand larceny is a legal term used to describe the theft of property or money exceeding a certain value, which varies across jurisdictions. Unlike petty theft, which involves smaller amounts, grand larceny carries heavier penalties—sometimes including significant incarceration and restitution obligations. The fundamental elements that constitute grand larceny are the unlawful taking, carrying away (asportation), of property, with intent to permanently deprive the owner of its possession.

In the historical context, the distinction between petty and grand larceny has been rooted in societal attitudes towards property rights and economic stability. The severity of punishment reflects the societal recognition that larger-scale theft damages economic order and trust more profoundly. Over centuries, legal systems have codified this distinction, with the value threshold as the pivotal variable. The development and codification of these thresholds often reflect local economic factors, inflationary adjustments, and policy priorities.

Nation-states and jurisdictions typically define grand larceny within their penal codes, with variances in the minimum monetary value to qualify the theft as ‘grand’. For instance, in many American states, the threshold might be set at $1,000—although this figure has often been adjusted over time to account for inflation. The complexity deepens as some jurisdictions distinguish acts of grand larceny based on the type of property—real estate, firearms, or commercial goods—while others maintain a uniform monetary threshold.

The Legal Definition and Its Nuances

Precise legal definitions often include specific language to eliminate ambiguity. For example, the Model Penal Code describes larceny as “the unlawful taking of moveable property” with intent to permanently deprive. When specifying “grand” larceny, the law integrates the value threshold, which is crucial for classification.

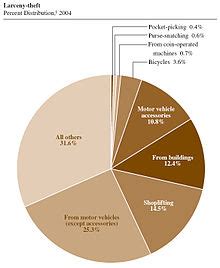

To illustrate, a typical statutory clause might state: “Grand larceny occurs when a person intentionally steals property valued at more than $2,000.” In this context, the value threshold constitutes the dividing line between petty and grand theft. It’s noteworthy that some jurisdictional statutes also incorporate categories based on the method of theft—such as shoplifting, embezzlement, or auto theft—each with their particular thresholds and legal implications.

Beyond the monetary aspect, additional elements include the intent to permanently deprive, the unauthorized nature of the taking, and the possession of stolen property. These factors are critical, as even a theft of high-value property might not qualify as grand larceny if committed under certain circumstances, such as if the taker believed the property was their own or had consent.

Jurisdictional Variations and Contemporary Applications

The concept of grand larceny fluctuates notably across different legal systems. In the United States, for example, each state maintains its own definitions and thresholds. California, for instance, classifies theft of property exceeding $950 as grand theft for misdemeanor purposes, with higher thresholds for felony classification. Conversely, in federal jurisdictions, the threshold often aligns with the federal monetary limits set in statutes like 18 U.S.C. § 666, which addresses theft or bribery concerning programs receiving federal funds.

In the United Kingdom, the terminology has historically transitioned from “larceny” to “theft,” with legislation such as the Theft Act 1968 and its amendments. The law emphasizes dishonesty and appropriation, with the value of stolen goods modulating the offense’s severity but often without a fixed threshold that explicitly categorizes “grand theft.” Instead, the severity of sentencing correlates with the value, in conjunction with aggravating factors.

In the modern legal landscape, digital theft and cyber-enabled fraud complicate traditional definitions. While the core principles remain—intent, unlawful taking, and property value—the transfer of assets in virtual environments challenges jurisdictions to adapt their legal frameworks. For example, some regions now consider digital assets, cryptocurrencies, and intangible property within their grand theft statutes, expanding the classical understanding rooted in tangible property.

Implications for Legal Practice and Enforcement

Practitioners must carefully analyze jurisdiction-specific statutes, especially regarding monetary thresholds and qualifying property types. When prosecuting, establishing the value is often a central piece of evidence, requiring detailed appraisals, witness testimony, or forensic valuation. Conversely, defendants may challenge the valuation or argue that their actions do not satisfy the elements of permanent deprivation or intent.

Law enforcement agencies employ various investigative techniques, such as surveillance, forensic accounting, and interviews, to substantiate claims of grand larceny. The classification significantly impacts case handling, potential plea deals, and sentencing outcomes. For instance, a theft valued at 2,500 in a jurisdiction where the threshold for grand larceny is 2,000 results in a more severe charge, often accompanied by longer sentences.

Legislative trends increasingly influence the scope of grand larceny. Some jurisdictions consider amendments to thresholds annually, reflecting inflation or economic shifts. Others expand the category to include specific property types or enhance penalties for repeat offenders, recognizing the societal costs of frequent thefts.

Historical Evolution and Future Directions

The concept of grand larceny traces back centuries, evolving from common law distinctions to complex statutory frameworks. Historically, “grand larceny” was often a felony punishable by heavy penalties, including branding, mutilation, or capital punishment, depending on the era and jurisdiction. Over time, legal reforms aimed to balance punishment severity with due process protections, leading to more nuanced classifications.

Advancements in technology and economic globalization are prompting jurisdictions to revisit definitions and thresholds. The rise of cyber theft, ransomware, and digital asset pilfering poses challenges to classical property frameworks. Experts argue that future legal structures might incorporate broader definitions encompassing intangible assets, with thresholds adjusted for the value fluctuations inherent in digital marketplaces.

Furthermore, ongoing discussions emphasize whether the value threshold remains a fair gauge of societal harm or if alternative metrics such as economic impact, recidivism risk, or victim harm should influence classification as grand larceny.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Grand Larceny

Understanding the detailed legal definition of grand larceny involves appreciating its roots, statutory variations, and contemporary adaptations. Its core relies on the theft of property exceeding a jurisdiction-specific value, accompanied by intent and unlawful possession. As societal circumstances evolve—particularly with technological advances—so too must the legal frameworks that define, prosecute, and adjudicate this serious offense. Practitioners, law enforcement, and policymakers continue to grapple with balancing clarity, fairness, and adaptability in defining what constitutes grand larceny in the modern era.

Key Points

- Precise threshold: The monetary value defining grand larceny varies between jurisdictions, often reflecting economic conditions and legislative priorities.

- Core elements: Theft of tangible or intangible property with intent to permanently deprive, combined with property valuation, determine classification.

- Legal evolution: Historical shifts from traditional common law to modern statutory language account for societal, economic, and technological changes.

- Impact of technology: Digital assets and cyber theft introduce new complexities, prompting legislative updates in property and theft law.

- Practical significance: Classification influences prosecution strategies, sentencing severity, and law enforcement procedures.

What is the typical monetary threshold for grand larceny in U.S. states?

+The threshold varies by state. For example, California sets it at 950, while New York historically used 1,000 but has adjusted thresholds over time. Overall, most states hover around the 1,000 to 2,000 range, with some higher thresholds for specific property types or felony classifications.

How has digital technology impacted the legal definition of grand larceny?

+Digital technology has expanded the scope of property considered in theft statutes, including cryptocurrencies and virtual assets. Courts are grappling with defining when digital property qualifies as ‘property’ under traditional laws and developing new legal standards to address cyber-enabled thefts, often elevating the importance of qualitative and quantitative valuation.

Are penalties for grand larceny uniform across jurisdictions?

+No, penalties vary significantly. Some jurisdictions impose long-term imprisonment, restitution, and fines, while others may have alternative sanctions. Penalties depend on the value stolen, prior criminal history, and whether other aggravating factors are present.

Can the thresholds for grand larceny be adjusted?

+Yes, legislative bodies periodically revise thresholds to reflect inflation, economic changes, or policy shifts. Adjustments often involve legislative bills, regulatory updates, or judicial interpretations to remain relevant and fair.